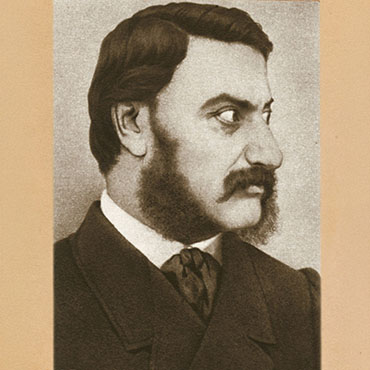

Coppino was born in Alba in the province of Cuneo in 1822, the son of a shoemaker and a dressmaker. He attended the local seminary, before obtaining a scholarship to the Collegio delle province in Turin, which enabled him to graduate in literature when he was little more than twenty years old. He taught rhetoric first in schools and then with a doctorate at the University of Turin, combining his literary activities with politics, a passion that always had a major role in his choices. He was close to the leftist ideas of Urbano Rattazzi, but not opposed to other views. At his first candidacy for the Liberal Democrats he did not win, but he showed his qualities in attracting the approval of voters, who sent him to Parliament after 1860, from then onwards for the constituency of Alba. He was also a member of the Freemasons of the Grand Orient in Turin and was inspired by ideals of liberty, social justice and service to the people, believing in an Italy that was independent and united, but strong because of the municipal structure that had marked out its history. From the very beginning he based his convictions on the role of state education as a driving force of the newly born Italian state, so much so as to start the academic year of 1849 with a lecture on Della educazione qual mezzo di nazionale Risorgimento. In 1861 he argued with Francesco De Sanctis, then Minister of Education, on the role of technical institutes, which, in his opinion, ought not to offer only a professional training, but should provide a broader cultural preparation.

He followed Cavour in the principle of a free Church in a free State and was also opposed to the Convention of September 1864 (which, in order to safeguard the papal lands, he would the move of the Italian capital from Turin to Florence). In the following years he took an active part in the debate about the Law of Guarantees [which regulated relations between Italy and the Holy See]. He was Minister of Education on and off for a few months in the second Rattazzi government and especially in many of the governments of Agostino Depretis, as well as for a short period in the first Crispi government.

He introduced a reform of primary schools, according to the principles of a free education extended to all levels of the population and signed a law for compulsory education in opposition to those who feared that through critical thinking a widespread education would endanger social stability. He was also concerned to improve the economic conditions of teachers and to fight against working insecurity. Obviously, his idea for reform of educational establishments could not be separated from a radical transformation of society, in the left-wing spirit of Depretis. Apart from educational policies, Coppino became involved in a wide-ranging commitment to protect the cultural heritage, through the passing of a law against the dispersal of works of art and historical documents, as well for the safeguarding and preservation of monuments. But the bill that placed obligations on those possessing cultural goods was defeated, because it was considered that it restricted the freedom of private citizens as regards the use of their property: this defeat led to Coppino’s resignation. As he did not agree with the authoritarian stance of Crispi, Coppino joined the opposition. He was elected among the ranks of the Liberal Democrats and voted for the government of Giuseppe Zanardelli, shortly before his death at Villa Rivoli near Alba in 1901. Besides some monuments to people of national importance and the creation of a Dante chair at the University of Rome, Michele Coppino sponsored the Galileo national edition. He was the one who in 1887 urged the King of Italy to issue the decree and to place the initiative under his own patronage. The process had not been short, slowed down as it had been by all sorts of problems, so much so as to cause Favaro to doubt several times whether it would really be possible to carry out his plan and whether the minister was really interested. The happy outcome of so many of his requests left him stunned when faced by what he considered an unexpected change: “[I have an appointment] at the Ministry – he wrote to Isidoro Del Lungo – where unfortunately I continue to spend most of the day always engaged in new work for this blessed enterprise of which Coppino has suddenly become an enthusiast. Can you imagine it – Coppino an enthusiast? Since he expressed the desire to see me before I left, I had a farewell audience with him yesterday, and took the opportunity to suggest to him to continue his patronage of the enterprise that he had approved: and he was very polite with me”.