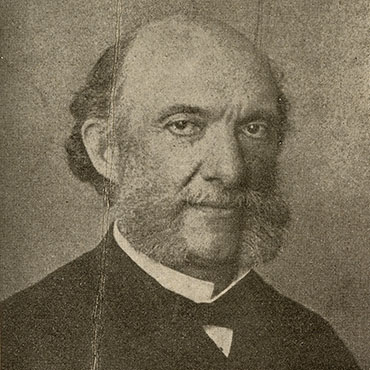

Govi was born in Mantua and studied at the local high school before entering the Law Faculty of the University of Padua, despite his early inclination towards physics and chemistry. In 1846 he decided to change direction and enrolled in the Faculty of Mathematics. He became active in the student movements, was involved in the uprisings and was made a student representative in the provisional government of Veneto. He took part in the first war of independence and fought at Sorio. He fled to Milan and then to France, a country to which he was attracted because of a particular interest in its language and in its culture that was a product of the Enlightenment.

He enrolled at the École polytechnique, where he studied chemistry with Edmond Frémy and Michel Eugène Chevreul, and trained in private workshops as a designer of scientific instrumentation. He became part of the scientific circles of Paris, where he got to know Guglielmo Libri, who drew him to the history of science, with special interest in Leonardo da Vinci.

On the invitation of Filippo Corridi, in 1856 he was given the chair of physics, technology and special technology at the Istituto tecnico di Firenze, where he was able to study the collection of manuscripts of Galileo and his followers in the Biblioteca Palatina. In 1860, after a short period as an officer in the corps of engineers in the Second War of Independence, he received the chair of physics at the Istituto di studi superiori, where he taught for one year, before moving to the University of Turin to teach experimental physics. In addition to his teaching work, which enabled him to make his contribution to the modernisation of the University’s laboratories, he also held various posts at national and international exhibitions, became a member of several academies and held a number of important roles on various bodies.

While Michele Coppino was a minister, Govi was asked to become a member of the ministerial committee that was intended to reform high school teaching, to sit on the board of archaeology and of the committee set up to list the autographs and the drawings of Leonardo, on behalf of which he studied the manuscripts in Milan. In 1870 he went to fight for the liberation of Rome from the forces of the Pope and was present at Porta Pia on 20th September. His support for the plan to make Rome a secular centre for scientific studies, a plan which he shared with well-known people like Stanislao Cannizzaro e Pietro Blaserna, did not result in his obtaining the first chair of the history of physical sciences in Italy, as he had hoped. However, he was made director firstly of the Biblioteca Casanatense, and then of the Biblioteca Vittorio Emanuele II. He spent a long time in Paris as director of the Bureau international des poids et mesures, and in 1878 he was made professor of experimental physics at the University of Naples. He was also a member of the major academic institutions in Italy, including the Accademia dei Lincei.

Despite holding numerous important posts for public administration, he was no lover of political involvement, which he saw as an obstacle to his research activities. These ranged from geometrical and physical optics, acoustics, the study of electricity and of temperature and experimental physics to studies in the history of science and publications of texts and documents, in particular those relating to Galileo and Leonardo (the manuscripts of Leonardo, which he had already transcribed, were never published in his lifetime).

When he was made scientific consultant for the national edition of the works of Galileo, he did not wish Raffaello Caverni to have anything to do with the project: he disagreed with Caverni, both in terms of his working methods and of his general vision of the world and mankind and he strenuously urged Favaro not to include Caverni in the working team (“Keep the priest away from the works of Galileo!”). This contributed, albeit unintentionally, to the break-up of a friendship that had lasted more than ten years. Gilberto Govi died in Rome in 1889.

In the anthology dedicated to him and published after Govi’s death to mark the start of the short collection “Vinciani d’Italia, biografie e scritti”, sponsored by the Istituto di studi vinciani in Rome, Antonio Favaro, praising his “wide culture” and the “elegance of his writing”, his thwarted commitment to teaching and his single-mindedness in research, his historical acumen and his political passion, acknowledged Govi as a master in his work on the manuscripts of Leonardo, despite the very limited and pioneering technical means that the times could provide. “Italy”, he observed with bitterness, “had in Govi the most profound scholar of the marvellous work of Leonardo and it will never be possible to regret enough that when it was finally considered to be right to make use of him, it was already too late”.