Lampertico was born in 1833 in Vicenza to a well-to-do family, whose sudden acquisition of wealth had attracted some gossip. After a period of private education, he studied at the episcopal seminary in Vicenza, where he was, among others, a pupil of Giacomo Zanella, with whom he would maintain a long and enduring friendship and whose biography he wrote. He then took up legal studies at the University of Padua, where he graduated in 1855. Even before his degree he was involved in local politics as adviser and councillor for the city of Vicenza. He was a follower of Rosmini through the influence of Zanella and showed a reforming bent that was expressed through charity work and mutual aid. He was active in cultural circles, like the Accademia Olimpica, of which he was a member, and, thanks to his acquaintances in the fields of economics and finance and also socially, he held positions in the Banca popolare di Vicenza and in the Chamber of Commerce.

He did not allow himself to become too involved in the passions of the Risorgimento, despite two pamphlets on the damages inflicted on Veneto by the economic policies of the Austrians: their anonymous publication protected him from charges of high treason. But once Veneto was annexed to Italy, the standing he enjoyed in the city, his connections with men of culture (Antonio Fogazzaro, incidentally, had married his niece) and with politicians of national importance, such as Marco Minghetti and Quintino Sella, facilitated his entry in 1861 into Parliament, as well as his election to the Provincial Council of Vicenza. He was a conservative but not averse to changes, Catholic but ready for conciliation, and was always willing to negotiate, inclined to a social order founded on property and free from conflict. Vicenza remained at all times the centre of his interests, in particular as regards the infrastructural development of the railway and the river port. He earned prestige and respect as a result of his indefatigable diligence in his parliamentary activities (mention must be made of his role as rapporteur for the commission of enquiry into the non-convertibility of banknotes in 1868). However, this prestige did not save his relations with his friends of the historical Right, which became broken as a result of certain disagreements that took him away from national politics for a time, even if, later on, it was Marco Minghetti who put forward his name for nomination in 1873 as senator.

In the period of his parliamentary “vacation”, he increased his literary production for special occasions and, above all, his works of an economic nature, which would later be the basis of the five volumes of his Economia dei popoli e degli Stati that appeared between 1874 and 1884. His scholarly activities attracted criticisms from a number of detractors, among the most vitriolic Antonio Labriola. In economics he was a free-marketeer, although he did admit that intervention by the State was necessary to protect interests. In order to uphold his ideas and defend them from the accusations that poured on him especially from the more radical free trade thinkers, he founded the Associazione per il progresso degli studi economici, making use of the “Giornale degli economisti”, that was its media outlet. His vision obviously resonated on his work in Parliament and brought him close to the left wing in the matter of economic policy and the method of constitutional reforms. Both Catholic and colonialist, he was a member and the president of the National association to aid Italian Catholic missionaries. Still in accordance with his ideas of “limited” free trade, he took an interest in agrarian policies and the management of flows of migrants.

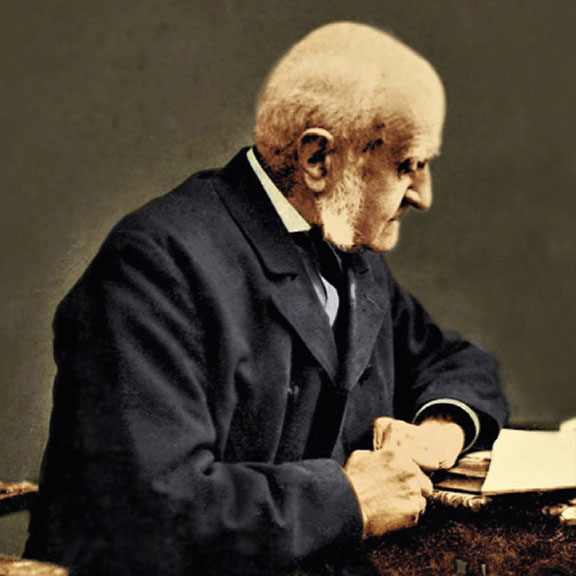

After a number of years scarred by family problems and ill-health, Fedele Lampertico died in Vicenza in 1906. In the eulogy at the Istituto Veneto, Antonio Favaro, as well as praising his gifts as a scholar, celebrated his vital initiatives as a fellow member, four times elected to the presidency, as well as his scientific contributions that had enriched the publishing activity of the Venetian institution. Several years later, when announcing to the Accademia della Crusca the publication of the last volume of the national edition, Favaro named him as one of the few figures that had made a decisive contribution to the success of the enterprise: “It was our friend Fedele Lampertico that repeatedly made use of his enormous authority to overcome the wrong steps that, given the changing attitudes of the administrations, unfortunately are found in work sponsored by the State”.