Wohlwill was born in Hamburg in 1835, but soon moved to the Duchy of Brunswick because of his father’s work. His studied first at the secondary school in Blankenburg, then at the Johanneum in Hamburg, where he was a pupil of, among others, Karl Wiebel, a teacher of physics and chemistry, who, as Antonio Favaro wished to stress, “instilled in him an appetite for considering inventions and discoveries from the point of view of their historical process”. His family also enhanced his education, providing him with a solid foundation of general culture, which his father himself, Immanuel Wohlwill, an active intellectual in Jewish circles, a friend of Heinrich Heine and a pupil of Hegel in Berlin, helped to develop, before his premature death left Emil an orphan at thirteen.

His pursued his university studies in Heidelberg, Berlin and Göttingen, where he graduated with a dissertation on the isomorphous mixtures of the salts of selenic acid. He would always remember the lectures of Johann Peter Müller on physiology, those of Eilhard Mitscherlich and Friedrich Wöhler on chemistry, the courses of physics of Heinrich Wilhelm Dove, Heinrich Gustav Magnus and Wilhelm Eduard Weber. After his degree, he deliberately returned to Heidelberg, where he continued his education with Robert Wilhelm Bunsen and Gustav Robert Kirchhoff, from whom he benefited so much that he remembered both of them with gratitude throughout his whole career.

Although he had been a political activist in the democratic ranks of the young Germans, once he became an adult he had no wish for a public position in his native city, where he had settled, but preferred to study and to teach scientific subjects and industrial applications. However, his decision to represent the Hamburg government at the 1873 World’s Fair proved to be instrumental for his profession, because the data collected on that occasion on the electrolysis of metals would be the basis for the so-called Wohlwill process, invented the following year and employed to refine gold and silver, which would give him some fame and a fair income. He was always keen to place scientific progress within its historical context, contrary to what one might infer from his technical responsibilities at the Norddeutsche Affinerie in Hamburg, and in 1865 for the first time he mentioned Galileo as part of a work on the history of the thermometer.

From the end of the 1860s Wohlwill waded into the controversy that had been going on for over ten years, triggered by the publications of the proceedings of Galileo’s trial. He openly sided with those who maintained that the documents produced by the Inquisition were false, although later the examination by Antonio Favaro showed them to be genuine, much to the explicit dismay of Wohlwill. However, Wohlwill had given proof of his abilities and his extensive preparation with an essay on the discovery of the law of inertia (which Favaro considered the best of his writings) and with two articles on Joachim Jung, scientifically based and historically documented. His project to write a biography of Galileo based on a detailed analysis of texts and documents led him to see at first hand the inconsistency of the editions published up to then, resulting in his great interest in the work of Antonio Favaro. Their collaboration was constant and more than once Wohlwill generously made a contribution of his own, as when he examined the letters of Matthias Bernegger, preserved in fact in Hamburg, or in the case of the “beautiful long letter” produced in his position as a corresponding member of the Accademia padovana di scienze, lettere ed arti for the booklet celebrating the tercentenary of Galileo’s chair at the University of Padua.

However, their different approaches as historians (extremely involved in the case of Wohlwill, so much as to overlook at times the rigour of interpretation, more neutral and “positively” focused in the case of Favaro) was at times the cause of discussions and disagreements. When in 1909 Wohlwill published the first volume of his Galilei und sein Kampf für die copernicanische Lehre it did not find total agreement on the part of Antonio Favaro. In particular, as regards the veracity of the Racconto istorico of Vincenzo Viviani, which Wohlwill considered to be hardly credible and essentially an apologetic, it started a dispute that lasted for years. Moreover, in the second volume, which neither saw printed in their lives, as it was published posthumously by the heirs many years later, Wohlwill had planned a detailed analysis of the querelle linked to the documents of the trial of Galileo, a querelle that years earlier saw him but taking a different side to Favaro. Nevertheless, the relationship between the two remained friendly, despite differences of opinions, and written contacts never ceased.

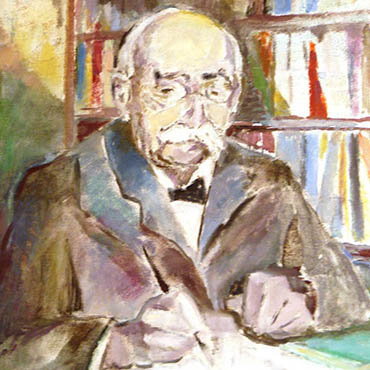

Emil Wohlwill died in Hamburg in 1912. He had been one of the founders of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Geschichte der Medizin und der Naturwissenschaften and had attended its meetings regularly. In his commemoration of Wohlwill at the Accademia di scienze, lettere ed arti di Padova, Antonio Favaro lamented the void left “in the small group of lovers of scientific history”, because “few had the ability like he had to penetrate into the historical reason for things, making original contributions to the various subjects to which he applied his mind, a mind that could be called subtly critical in the strictest sense of the word”.