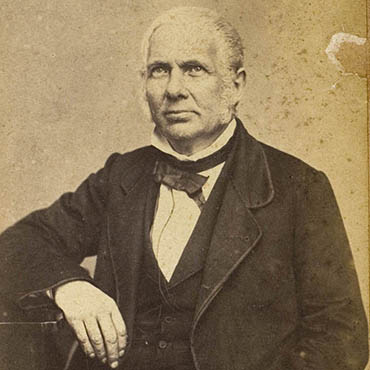

Bellavitis was born in 1803 in Bassano to a hard-up family and was educated at home. He then followed his father’s steps as an employee of the local council, while, at the same time, teaching himself mathematics, with little money and few books, which he often borrowed and copied by hand. While he was still young, he made a name for himself through some not insignificant publications in the field of mechanics. With the financial support of the Istituto Veneto di scienze, lettere ed arti, he taught mathematics and elementary mechanics at a high school in Vicenza. Subsequently in 1845 he was awarded the chair of descriptive geometry in the University of Padua and in 1867 that of complementary algebra.

For three years he also taught physics, with notable success in experiments. Among his writing mention must be made of Calcolo delle equipollenze (1835) (which, however, was not well received by his colleagues), Saggio di geometria derivata (1838), Lezioni di geometria descrittiva (1851), Lezioni di gnomonica (1869), as well as numerous articles (those on third-order curves, Hamiltonian quaternions, algebraic equations and some on analytical geometry are particularly important), mostly published by the Istituto veneto and in the “Annali di scienze matematiche e fisiche” of Barnaba Tortolini. His style, which was quick-witted and acerbic, often provoked arguments, frequently bitter, with friends and colleagues, where he lashed out against all the new frontiers of mathematics, especially non-Euclidean geometry.

In his article, written in German in the “Historisch-literarische Abtheilung der Zeitschrift für Mathematik und Physik” of Leipzig, Antonio Favaro remembered him with respect and affection, even when criticising him. He wrote that Bellavitis’ work ranged over a very wide spectrum of fields: philosophy, pedagogy, social sciences, arithmetic, algebra, superior analysis, elementary geometry, descriptive geometry, plane, spherical and solid geometry, probability, mechanics, hydraulics, general physics, thermodynamics, optics, theory of electricity, astronomy, chemistry, mineralogy, plant physiology, zoology, microbiology, meteorology, practical geometry, theory of art, geography, history of literature and bibliography.

Bellavitis was a member of many European academies, including, from 1879, the Accedemia dei Lincei. Despite spending a life that was in no way cosmopolitan, he had learnt perfectly a number of languages, which enabled him to acquire a deep knowledge of the scientific production of the greatest European mathematicians. During his years teaching in Padua, Giusto Bellavitis had seen Antonio Favaro mature as one of the students at the University of Padua and some time afterwards they became colleagues. Favaro acknowledged that Bellavitis had a real vocation for teaching, so much so that he considered the time of his sudden death, that happened in Padua in 1880, was one of the best in his life: sitting at his desk with his hand on the blackboard, like a good soldier, with a bullet in his chest, facing the enemy.