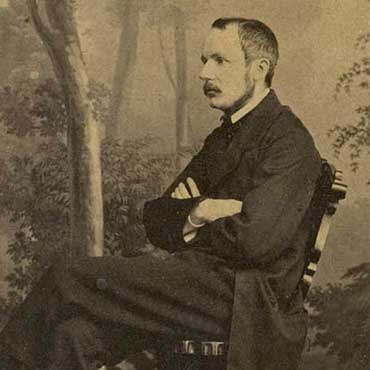

Baldassarre Boncompagni, the son of Luigi, Prince of Piombino and of Maddalena Odescalchi, was born in Rome in 1821. After his early studies, which led to a special relationship with Barnaba Tortolini, teacher of differential and integral calculus at the Sapienza University, at the age of eighteen he started to show his interest in history, with articles for the “Giornale arcadico di scienze, lettere e arti”, which in 1846 also included his publication Intorno ad alcuni avanzamenti della fisica in Italia nei secoli XVI e XVII.

He was called to become a member of the Accademia pontificia dei Nuovi lincei, founded by Pius IX, and he took on the role of secretary. In 1851, in the “Atti” that the Academy published, he started the long series of historical studies on medieval mathematics, which ranged from the translations of Plato Tiburtinus to biographies of Gerard of Cremona, Gherardo da Sabbioneta and of the astrologer Guido Bonatti and to various works on Leonardo Fibonacci and editions of his writings, as well as the publications of various arithmetical treatises, including those of Johannes Hispalensis.

From 1868 onwards, totally at his own expense, he edited the “Bullettino di bibliografia e di storia delle scienze matematiche e fisiche”, which in almost twenty years of life brought together the major writers of the history of science, both Italian and international. Antonio Favaro, although acknowledging excessive erudition bordering on pedantry, remembered the beneficial effects on other authors, who were also driven to greater rigour in working on documents.

Feeling that his health was beginning to show signs of failing, Boncompagni had thought of entrusting the management of the journal to Favaro himself, but because Favaro had taken on the maelstrom of work for the national edition of Galileo, he was forced to turn it down.

Boncompagni was a member of a variety of academies, both in Italy and abroad, but he did not wish to become a member of the Accademia dei Lincei that had been founded by the Italian state, having been an important figure in the Papal equivalent. He also refused the offer by Quintino Sella of a seat in the Senate.

Prince Boncompagni died in Rome in 1894, having spent the last years of his life organising his own library, a library considered by Favaro unique in the world, being the outcome of investments worth millions. But neither the proposal to donate it to the city of Rome nor the attempt to have it accepted by the Vatican was successful. Once it had passed to his heirs, the collection was broken up.

As far as Antonio Favaro was concerned, the “Bullettino di bibliografia e di storia delle scienze matematiche e fisiche” was a training ground of reports and studies: he published his first historical article in it and contributed articles for a long time. As for Baldassarre Boncompagni, Favaro praised him not just for his generosity in financing, out of his own pockets, a journal that was for its time unique of its type, but also for his almost fanatical care with which he dealt with the documents and acknowledged the vital role that Boncompagni had played in his own training as a scholar of original sources.