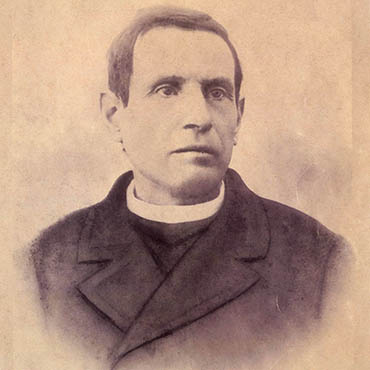

Caverni was born in 1837 into a very large and very humble family in San Quirico di Montelupo. He showed an urge to learn from an early age and was admitted as an aspirant priest in Florence Cathedral, later attending the Collegio Eugeniano and the Scuole Pie of San Giovannino, where he was taught by the most important Piarists of the time. In addition to philosophy, physics and mathematics, he studied astronomy at the Osservatorio Ximeniano and chemistry at the Istituto tecnico. At the end of his course of studies he was asked to teach philosophy, theology and mathematics at the seminary in Firenzuola, where, in 1860, he was ordained priest and where he would stay for more than ten years.

He soon became known for some observations concerning the scientific notes of Giovanni Antonelli on the Divina commedia with comments by Niccolò Tommaseo. These observations were never published, and neither was his plan for a phonograph described there, a plan which had never been followed up. In 1871 Caverni was appointed to the parish of San Bartolomeo a Quarate, a rather isolated village in the valley of the Ema, where he spent the rest of his life. However, this isolation did not prevent him from carrying on concurrently both his studies on original manuscripts held in the Biblioteca Nazionale in Florence and his popular scientific work published in specialised journals or books for schools.

In 1875 he started a relationship with Antonio Favaro, who had contacted him for information regarding a short anthology of texts by Galileo printed the previous year. The friendship between the two men was cemented following the publication of the short book De’ nuovi studi della filosofia: discorsi di Raffaello Caverni a un giovane studente, which had already appeared in instalments during the previous years in the “Rivista universale”, in which Caverni attempted to reconcile evolutionist theories with Catholic doctrine, and accused the theologians – with particular severity towards the Jesuits – of unjustifiably impeding the progress of science. The work was received by the Catholic hierarchy with disapproval and suspicion and it was placed on the Index in 1878. Caverni had to accept formally the decisions of the Sacred Congregation.

While he continued his work on the sources as well as his educational activity, collaborating on the one hand with scientific journals such as the “Bullettino di bibliografia e di storia delle scienze matematiche e fisiche” of Baldassarre Boncompagni, and on the other hand with educational magazines for families, young men and ladies, he became also involved through Antonio Favaro in the plan for the new edition of the works of Galileo. For this he was given the tasks of providing the texts with a commentary and of arranging Galileo’s works de motu, in agreement with the publisher Le Monnier, for whom he had already written for the series “Biblioteca delle giovanette”. It was Antonio Favaro again who urged him to take part in the Tomasoni competition, launched by the Istituto veneto di scienze, lettere ed arti for the best work on the history of the experimental method in Italy.

However, nothing went according to plan. Le Monnier was replaced by the publisher Barbèra, the ministry decided that the edition should not have any commentary and the scientific consultant Gilberto Govi put a veto on the name of Caverni. Caverni blamed Antonio Favaro for what had happened, cooling their relationship and gradually ceasing all forms of collaboration. Not even a favourable review by Antonio Favaro that enabled Caverni to win the Tomasoni prize, could clear the air, as he was also annoyed by the regulation that the prize could only be actually given after printing had taken place. The result was that Caverni decided to end all contacts from then on.

In the following years he published in five volumes (plus a sixth published posthumously) his Storia del metodo sperimentale in Italia, which included alterations to the original text presented to the Istituto Veneto and harsh criticism of the volumes of the Opere di Galileo Galilei that were being published at the same time. Antonio Favaro eventually became aware of this and decided not to reply to the attacks made on his edition, as well as on “his” Galileo, and from then on Favaro called Caverni “the honest prior”. Only many years later did he mercilessly put Caverni in the Adversaria Galilaeiana, placing him, without even mentioning his name, under the title Scritture galileiane apocrife, because of a series of “rigged” texts published as genuine in volumes 5 and 6 of the Storia. Raffaello Caverni died in the vicarage at Quarate in 1900.